This is a piece in progress. I did a writer's workshop with MJ Hyland earlier in the year, and she gave me some feedback on this piece, which I would like to use when editing. In the busy-ness of life, however, I haven't had the opportunity to sit down and heed her wisdom. But I will...

In the meantime, her is version 1 of The Key and stay tuned for future, tighter versions. Let me know what you think.

Zannix

The Key

Lucy found a swipe card on the floor of the laundry one evening. She stifled it in her pocket – this key will change our lives, Lucy declared. It came down to that. That's how desperate we were.

We told Viv, and no-one else. The three of us waited until lights out and for Hucho, the boarding mistress' footsteps to cease. Lucy swiped the card. The green light came on and the monitor beeped once, twice. Gently, Lucy pushed open the door, a millimetre at a time so it didn't squeak.

And...we were out.

“Let's go on the roof,” decided Lucy. Viv produced a pack of cigarettes from the pocket of her hoodie, which she danced in front of us.

The cool night air smacked me in the face as we let ourselves onto the roof. My nervousness turned to exhilaration. We were free! I hadn't felt the night air, so cold and clear, forever.

We watched security from our watchtower as he patrolled with the old German Shepherd, called Edward. Security was for our own safety - to keep the predators out, or something. Viv lit up, and passed it round. I don't like smoking, but I inhaled, coughed, gagged, and passed it on. We talked about the social, about Maths with Kerry Cretin, and of course about Cauldy. Alex Caulder was a guy from the boys’ school down the road. He was tall, and bulky, from a property in Western Queensland, and drove a Holden ute with an enormous bull-bar attached and stickers like “Honk if You're Horny” plastered to the back window. Lucy was in love with him, but they had never even had a proper conversation.

The swipe card defined us, and gelled us. Every morning we sat together at breakfast, more tired than the others, but proud and pleased with ourselves. We had an out. A key to our freedom, and the others were all doomed to sit obediently and do as they were told.

We sprayed deodorant on our clothes so no-one detected the smell of cigarettes.

Lucy was the first girl I met when I arrived in Year Eight. I came to the school a year later than most people. Friendship groups had already formed, and I just tagged on the end. Only Lucy embraced me. She invited me to her table, where we sat at recess and lunch. On Year Eight camp, she asked if I would be her buddy. Lucy saved me. She was so popular, so well liked. Everyone looked to her for everything but, for some reason, she chose me.

She invited me home to her family's property for weekends occasionally. We were allowed two weekend leaves a term. My parents lived in Hong Kong, so I never went home between holidays. Lucy lived on a huge sheep station eight hours drive from school. Her parents were warm and loving, and her mum made home-made chutney and jam, and sent me back to school well-fed, warm and well-loved.

Viv arrived the beginning of Year Eleven, the only new boarder that year. Viv was a city girl, expelled from her school in Sydney for drinking alcohol on a ski trip, and various other offences. Viv came to our school not caring about making friends, or fitting in. She just wanted to get through the next two years, and then get out, and do exactly as she pleased. She wanted to be a fashion designer. She recycled clothes from op-shops, tearing them to bits, and re-stitching them. And she had her nipple pierced. The other girls avoided Viv – a bit too out there, too sure of herself. She intrigued me though, and Lucy, as Lucy was prone too, took her under her wing. Even though Viv didn't need anyone, I think she was secretly pleased Lucy made room for her on the lunch table.

The term passed by. No-one else knew about the swipe card. We smoked two packs between us throughout the term. At some point, we smuggled a bottle of vodka under Viv's hoodie that her mum had bought duty free. We played games on Lucy's iPhone, and wrote dumb things on Facebook walls.

But sitting, chatting on the roof, cold, shivering and sometimes wet, soon lost its appeal. Especially as no-one knew how dangerous we were being. We started to graduate. Climbing from roof to roof, until we nearly were out of school bounds. The security guard never looked up, his eyes peeled for prowlers outside the school gates.

One night, Viv slipped on a loose tile. My heart flipped, and I shrieked. But she stopped sliding before she reached the gutter. She and Lucy were sniggering, and soon became hysterical. I tentatively suggested we give the roof trips a break for a while. Anyway, Maths exams loomed. English assignments had reared their ugly heads. I think Viv went up for the occasional cigarette, but Lucy and I didn't go up for the rest of the term.

Lucy invited Viv and me on holidays with her to the beach. A crew were going, and renting a cabin at the beach-side caravan park. I opted for this sort of “fun” holiday, rather than going home to Hong Kong to see Mum and Dad, who would probably be too busy with work to see much of me anyway. Viv declined the invitation. She hated the other girls who were going.

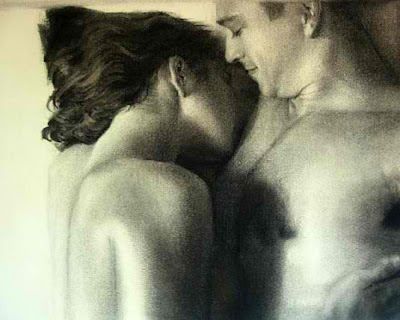

We spent the holidays drinking, smoking and skinny-dipping. A crew of boys from our brother school were staying at the same park, and hung around most nights. Incidentally, Cauldy was one of them. When we arrived and saw his ute parked out the front of one of the cabins, I felt Lucy's fingernails in my arm. One night, after a bottle of O.P. rum and skinny-dipping in the sea, Lucy didn't come back to the cabin. Her bed next to mine was empty all night. The next morning, I sat out the front of the cabin reading a magazine. Lucy emerged, almost literally from the bushes. Her face was streaked with dirt, a grin tweaked the corners of her mouth. Sort of bashful.

“Me and Alex did it in his ute,” she announced, mildly. Somehow, I felt proud of Lucy. She was not the first of the group to lose her virginity, but I knew what this meant to her.

“What was it like?” I ask shyly.

“It was OK.” And that was the end of the conversation about sex with Alex Caulder.

I wish I could have stopped the clock at that holiday, gone back and spent the rest of my life in the cabin with Lucy and the three other girls, hanging at the beach. I wish we hadn't gone back to school that term.

The term started like all others. A low down of the end of term assessments. Pressure was building for the big end of Year Twelve exam, and they were trying to make us sweat, and work harder. The boarders had a special BBQ to welcome us back after holidays, and they gave us ice-cream paddle-pops for dessert.

The weeks ground on. We hadn't been on the roof after lights out all term. It was like we had forgotten. Then one night, after a hellish day in Maths, Lucy knocked on my door. I opened it, and a blue vodka lid peaked round the corner.

“You game?” invited Lucy, teasingly. I pushed my Maths homework away, and followed the blue lid. We passed Viv's door, and Lucy knocked. No answer. She shrugged, and led me up to the roof.

Warmer now. Summer was setting in. The concrete was still warm from the heat of the day.

“Fuck I hate Cretin,” sighed Lucy, swigging from the bottle. “She's such a cow. She makes my life so miserable.”

“Yeah,” I commiserate. “She's so bitter. She's been at the school forever and has no life except to torture us.”

“Yeah.” We passed the bottle between us, then Lucy produced a cigarette, bent, from her pocket.

I loved being up there with Lucy. Always, since the first day in Year Eight, she made me feel so included. Special.

“Coming?” Lucy pulled herself up onto the ledge. “I'm going to try and get onto the roof of the chapel.”

“No way, that's way too high”.

“Nup – I know how to do it. I worked it out in R.E. today. Cinch.”

Now I really was scared. The vodka was burning in my throat.

“OK,” I followed her up onto the next roof top. I didn't want her to go alone.

We scaled each roof, slowly. Laughing nervously as we slipped a little, and grabbed onto the nearest tile. Until we were at the chapel. There was a gap between the roof we were on and the lowest gutter of the three-storey chapel roof. Concrete steps bridged the walkway between the buildings.

“Hold my ankles,” Lucy instructed. She handed me the box of cigarettes she had in her hand, which I stuffed in my pocket.

She knelt and leant forward, stretching. And then she did it. Grabbed the gutter of the chapel.

“Got me?” she said in a loud whisper. I nodded. And she pushed off with her feet, and next thing was dangling off the gutter from her fingertips.

“Luce!” I hissed, scared witless. But she didn't respond. She was hanging for a second, and then...she slipped, her fingernails of one hand scrabbling for the gutter, making a back-tingling scratching sound.

“Lucy!” I yelled, desperate. She didn't catch it, and she fell. She fell.

I watched her, stunned. It took forever. She landed face down on the concrete steps. A solid heavy thump. I couldn't move. Then I screamed. I screamed and I screamed. And I scrabbled as fast as I could to the lowest part of the roof, lowering myself down onto the roof of the walkway, then jumped and landed in a hibiscus bush. My head was whirring. I was drunk, and out of breath. I was numb with pain. I raced to where Lucy's body was lying. Falling over, as I stumbled on the stairs. I got up and reached her, lurching myself onto my knees. “Lucy!” I screamed. “Lucy!” She didn't respond. She was not moving. I lightly touched her back. She was not breathing. I didn't know what to do, and I couldn't think. Suddenly I heard footsteps. The security guard was there, panting.

“What's going...?” he stopped when he saw Lucy's body.

It all happened in a blur. Hucho came down, the ambulance arrived. Girls were huddled together in their pyjamas. Crying. Wailing. Three men lifted Lucy's body onto a stretcher, then covered her with a sheet. I turned away. It was too devastating. Too much to take in. I stood by myself, not crying, not wailing, just watching the ambulance drive out the school gates. Horrified, and silent.

The next morning, I still hadn't shed a tear. And then it occurred to me that I would probably be suspended – expelled! For being on the roof. For drinking alcohol. For letting Lucy... Gaol, even, was a distinct possibility. I imagined myself hauled into the back of a paddy wagon, cuffed, everyone watching on.

As everyone dispersed into their respective classrooms for first period, Reverend Lucas came up behind me and tapped me on the shoulder. I followed him to his office. He asked how I was feeling about what happened. I said I didn't know. He asked me why I was up on the roof with Lucy – what had happened to Lucy yesterday, how had she been feeling, had she said anything to me about why? I sat back and looked at the Reverend. I was shocked – did he think...did they think that Lucy had jumped off the roof?

“Lucy was happy!” I yelled. “We were up on the roof because we wanted to, because it was something a bit different. Something fun!” He looked at me doubtfully, and said nothing in response to my sudden outburst. He removed his spectacles, and wiped them with a tissue.

“Louisa, you will of course be offered counselling to help you deal with what happened, and any additional tutoring you require to get you through until the end of the year. There will be a police enquiry, and you may be required to be a witness – but I will continue to support you throughout. ”

I was silent. All I could imagine him saying next was that I would be expelled, at the very least.

“Louisa...” he paused, dramatically, “it will all be OK.” He looked like he meant it – like he was sure it would.

I wished I had been expelled that day. Sent back to Hong Kong on the first plane out. Fined, stoned, tortured in some horrible way. Instead I faced...what, exactly? Girls in the classroom exchanging glances, occasionally someone touching my arm, as if in sympathy, but no-one, no-one ever talked to me about Lucy. Except the counsellor of course. But she seemed more preoccupied with my emotional stability than Lucy herself, and exactly what happened that night. Even Viv, for the first time in her life, was lost for words. She looked at me with this pained face, as if to say: “I wish I knew what to say.” But like everyone else, she apparently didn't.

Like the counselling sessions, the inquest seemed scripted, as if it were written in the manual. Dressed in my blazer, stockings and a hat, I was escorted into town by Hucho in a maxi taxi, and interviewed about my relationship with Lucy and my account of the event. The coroner questioned me extensively about the exact details of the fall, and sat back in his enormous chair when I finished, as if I had given the correct answer, and he was happy. The autopsy revealed nothing unusual that indicated foul-play. The coroner ruled Lucy's death was accidental, and I was escorted back to school. He may as well have ruled me guilty of murder.

The funeral was held in Lucy's home town ten days after the fall. The school took a bus of us girls, and gave us two days off school. Viv refused to come – she said she hated funerals. I saw Lucy's mother sitting in the front pew, wearing dark glasses, and a huge navy sun hat pulled over her face. I remained at the back of the chapel, behind a pillar. Alex Caulder was standing close by with a mate, dressed in a suit, his thick black hair slicked back, smartly. Lucy's brother spoke at the funeral. He thanked everyone for coming, especially those who travelled to be there. Drinks and snacks were provided after the service, and accommodation expenses at the local hotel had been taken care of, he said. They played Amazing Grace, and Lucy's favourite song – a country song about horses with wings. I didn't cry. Behind the pillar, I stood motionless, staring at the coffin.

Later, as the wake was winding down, and waiters were clearing glasses, I felt a presence behind me. I looked around. Lucy's mum stood alone, in her navy suit. She removed her glasses – her eyes puffy and swollen.

“Louisa, I just want to say...” her voice quavered. “I just want to say...” She looked at me, pleadingly, willing me to read her mind, finish her sentence for her. But I drew a blank. I didn't know what to say. How could I ever put into words how I felt – or didn't feel? We stared at one another for what seemed like a lifetime, and then suddenly, her face closed, and she walked away, hurriedly, as I said, “I'm sorry,” my voice cracking, and shadowing her, like an echo.

Back in my dorm, my door locked and phone off the hook, I couldn't study any more. I couldn't think. I could only sit there vacantly. I turned the cigarette packet over in my hand. It was crumpled, and nearly empty. I thumbed the cigarettes, then realised that the swipe card was also in the packet. Pulling it out, I examined it. That damned swipe card. That golden, tormenting and torturous key – why did it ever come into our lives?

The next morning, when it was still dark, I left. I packed everything I owned and rang a taxi. I stopped at Viv's door – the one person who might miss me, and be sorry to see me go. But I didn't linger, and before anyone was even awake, with my precious swipe card I let myself out of the front door, and the front gate.